by Maeve Kerr-Crowley

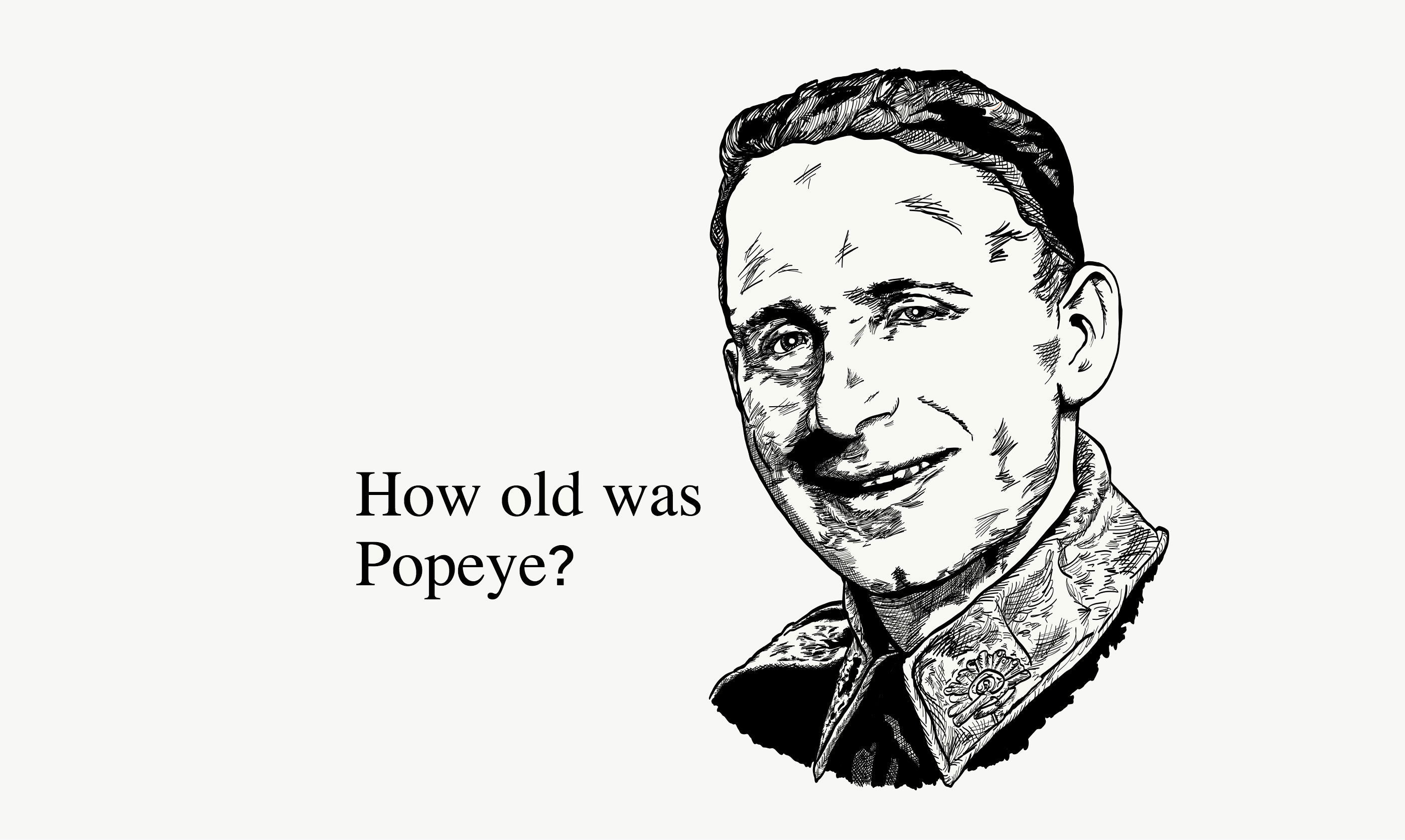

Depending on when you asked him, Francis 'Popeye' Crowley had three birthdays. In his 75 years of life, Frank changed his age twice. Once to make him older, once to make him younger. He lived in two countries and fought in two world wars. He had seven children, one wife, and no luck catching fish.

Frank was born on the 5th of July, 1901 in Manchester, England, into an Irish Catholic family with a strong military history. Frank’s grandfather, Charles Keys, fought in the Crimean War, which lasted from 1853 to 1856. At the time of his death in 1914, Keys was one the last five survivors to have served in the war.

Keys’ son in law and Frank’s father, Charles Crowley, fought in the Boer War, Burmese War, and First World War. After serving in the Battle of Ladysmith in the Second Boer War, Crowley Senior was rewarded for his gallantry and made a Queen’s Sergeant.

So it was no surprise that Francis himself was one of an estimated 250,000 young boys who upped their ages to fight for Britain in the First World War. When the war broke out on the 28th of July, 1914, Frank was only 13 years old. This was well below the enlistment cut off of 19, but like many boys his age he was not turned away by an army desperate for willing soldiers.

Unlike many of those boys, Frank survived the war. He’d fought with the Rifle Brigade, an infantry rifle regiment in the British Army formed in 1800. During the First World War, the Rifle Brigade was made up on 28 regular battalions, and 11,575 of its members died in action.

After the war ended in 1918, Frank did jobs in Gibraltar and India before moving to Australia.

He moved to a town called Avoca, 71 kilometres from Ballarat in the Central Highlands of Victoria. Unable to find work in the area, he then travelled 400 kilometres to Mildura, where he took on an assortment of odd jobs to make a living.

Returning to Avoca, Frank married a woman named Laura, found a job, and was able to support his growing family for a few good years.

But Australia was hit hard during the Great Depression, with unemployment peaking around 30% in 1932. Homelessness rose sharply, shanty towns emerged, and roughly 60,000 people were receiving sustenance payments, known locally as the ‘susso’.

Frank and his family were among these, receiving about $5 a week. This is the equivalent of about $200 today to cover Frank, his wife and their seven children. Again, he tried everything he could to get work, taking any small job that came his way. But in the end, like many men with families to support, Frank decided the only thing he could do was enlist.

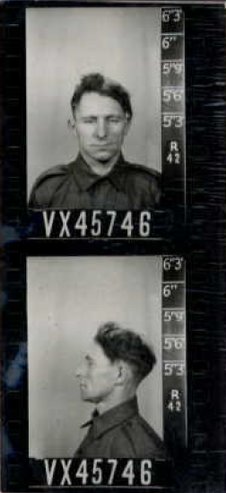

He enlisted on the 26th of June, 1940. At the time, he was 38 years old, 5 feet 7 inches, missing two joints from his little finger, and was declared fit for service. He would once again fight in a World War, but this time for the Australian Imperial Force.

Frank was deployed to the Middle East and served as a Sapper, a soldier responsible for tasks like building and reparation, or laying and clearing mines. But there’s very little his family knows about his time there. Like a lot of returned servicemen, he never spoke about the places he’d been or things he’d done during the war.

When World War II ended in 1945, Frank was discharged with the rest and returned home to Avoca. While relatively unscathed, he’d been left with bad rashes up his legs from the trenches. The local doctor had him sent to the repatriation hospital in Melbourne, telling him that if he was offered any money at all, he should take it. No matter how low the amount, even if it were a penny, he told Frank just to offer was them taking responsibility for his injuries.

And he was offered money. The hospital offered him sixpence a fortnight and were shocked when he said he’d take it. Sixpence was nothing, but Frank was a cunning man, smart enough to find the advantage in the situation. This sixpence later rose to $2.50 a fortnight after decimal currency was introduced in 1966.

With a large family depending on him and his military wage over and done with, he still faced the issue of having to find a job. Unemployment levels post-war were low, but with an influx of healthy working men returning to the workforce, Frank found himself struggling.

Initially he took up work on a dredge on the Avoca River in Amphitheatre, a town settled in the 1850s after the discovery of gold in the area. Both Frank and his eldest son Joe were employed in Amphitheatre for a few years before the dredge stopped running and they were both out of a job.

His next job was at P&N, a toolmaking company operating out of Maryborough since the 1920s. Frank, always a hard worker, was one of several Avoca men working for P&N. And after many content years of toolmaking and money earning, the issue arose that nobody seemed to be retiring.

Employers requested that their workers produce their birth certificates. Frank sent off to England for his papers, and when they came he was immediately let go.

Frank’s birth certificate had revealed that he was 71 years old. Not 64, as he’d told his employers. When work on the dredge had dried up, Frank had changed his age to increase his chances of getting a job. He’d gotten away with it once before, why wouldn’t he try again?

After doing everything in his power to avoid it, Frank’s working life was over.

Francis Crowley was a friendly, beer loving man, a good boxer, an excellent gardener, a charming entertainer, an enthusiastic but untalented fisherman. And after a life spent doing everything he could to support his family, he died of a heart attack at the age of 75. He was buried in the Avoca Cemetery with his wife Laura. They played the Last Post at his funeral, and you can guarantee there wasn’t a dry eye in the house.